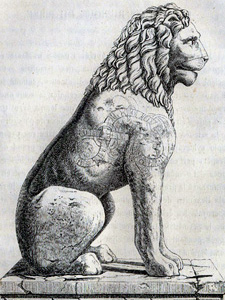

The Venetian Arsenal is guarded by four statues of lions. One of them, a nine feet high marble beast, bears on its mighty shoulders two lengthy runic inscriptions. These are carved within the intricate ornaments that represent writhing lindworms, characteristic for classical runestone design. The holy patron of Venice is St. Mark; the vicissitudes of fate that brought the lion, St. Mark’s symbol, to Venice, deserve some consideration. In 1687, during the Great Turkish War, Athens were besieged by Francesco Morosini, Venetian naval commander, who, beside being victorious over his enemies and damaging the Parthenon by the cannon fire, did not hesitate to pillage the city. Among other trophies he brought home two marble lions that decorated the Piraeus harbour of Athens since the first or second century AD. One of them was covered by the signs that no one could understand.

The Venetian Arsenal is guarded by four statues of lions. One of them, a nine feet high marble beast, bears on its mighty shoulders two lengthy runic inscriptions. These are carved within the intricate ornaments that represent writhing lindworms, characteristic for classical runestone design. The holy patron of Venice is St. Mark; the vicissitudes of fate that brought the lion, St. Mark’s symbol, to Venice, deserve some consideration. In 1687, during the Great Turkish War, Athens were besieged by Francesco Morosini, Venetian naval commander, who, beside being victorious over his enemies and damaging the Parthenon by the cannon fire, did not hesitate to pillage the city. Among other trophies he brought home two marble lions that decorated the Piraeus harbour of Athens since the first or second century AD. One of them was covered by the signs that no one could understand.

It is only a hundred years later that the inscriptions were identified as runic by Johan David Åkerblad, Swedish diplomatist. However, already by that time several fragments of the carvings were destroyed by erosion, so that deciphering and translation were barely feasible. Attempts to read the texts abound, but hardly any one of the interpretations might be relied upon.

Nowadays, the runes and the ornaments almost disappeared, the Viking Sphinx still keeping its secret. Yet the main message is quite intelligible: the bold Varangians intended to say, “Kilroy was here,” thus proving the phrase “Athenian Vikings” not to be as unlikely as one might believe.

Image: Monuments runographiques. Copenhagen, 1856.

This is an awesome story. May I ask where the illustration came from? Would be great to include in a book I am editing for Taschen titled “Trespass: Uncommissioned Public Art”.

The illustration is from C. C. Rafn, Antiquités de l’Orient. Monuments runographiques, published by la Société royale des antiquaires du Nord, Copenhagen, 1856.